WEB160 » Writing Effective Headlines & Paragraphs

Users want to find that one and only paragraph they are interested in. In this case we need to lead users to that paragraph. Therefore, our text becomes much like street signs that will lead us to the location we are looking for.

Creating Meaningful Headlines

Paragraphs (or set of paragraphs) should be separated by meaningful headlines that will give the online reader the overall idea of each paragraph:

Headings and subheadings should:

- mark the trail to the information that your users are looking for—users will become lost if the headlines to your paragraphs do not mark their way

- allow the user to skim through the page—let the user decide whether they want to read the paragraph(s) or not

- announce a new topic or new idea within your page

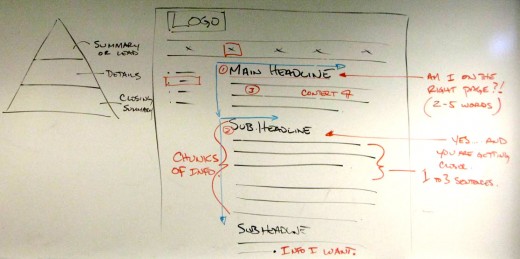

By breaking your articles of information up into two or three levels of meaningful headings (supported by topic oriented paragraphs) you will help your reader to scan your page:

This is called using the “F-Pattern”:

See Also:

- F-Shaped Pattern For Reading Web Content | Jakob Nielsen’s Alertbox

If the sub-topics of the paragraphs that follow the topic headline are associative to the main idea, the paragraphs will bee seen as a cohesive group that supports the main idea.

As a result the online reader will be able to organize how each topic and sub-topic fits into a structure:

Before:

MRP can handle two kinds of manufacturing—discrete and repetitive. They differ in regularity and costing. When you need to make products in groups or batches, you use discrete manufacturing. You give each batch a job number, a manufactured part number, a quantity (for that particular job), a start date and end date. Because you have a discrete job, you can charge all production costs to that job. With job costing, you can open a job, collect the charges for a job, close out a job, analyze and report costs and variances by job. On the other hand, you may have to manufacture some products continuously. Instead of discrete groups, you have a nonstop flow of products through the line. You define your schedule by the daily rate of production, and you charge the cost of production to the product, on a lump or unit basis. You never close out a schedule; you just vary the rate of production. So you analyze costs by period; when the period closes, you total all charges, and divide that number by the number of products, to get a unit cost, and usage variances, during that period. You choose one method or another for a product when you set it up in the inventory. From that point on, MRP will plan production based on the method you have chosen—discrete or repetitive.

After:

We Can Handle Two Kinds of Manufacturing

MRP can handle two kinds of manufacturing—discrete and repetitive. They differ in regularity and costing.

Discrete Manufacturing Works in Batches

When you need to make products in groups or batches, you use discrete manufacturing. You give each batch a job number, a manufactured part number, a quantity (for that particular job), a start date and end date.

Costing: Because you have a discrete job, you can charge all production costs to that job. With job costing, you can open a job, collect the charges for a job, close out a job, analyze and report costs and variances by job.

Repetitive Manufacturing Just Goes On and On

You may have to manufacture some products continuously. Instead of discrete groups, you have a nonstop flow of products through the line. You define your schedule by the daily rate of production, and you charge the cost of production to the product, on a lump or unit basis. You never close out a schedule; you just vary the rate of production.

Costing: You analyze costs by period; when the period closes, you total all charges, and divide that number by the number of products, to get a unit cost, and usage variances, during that period.

You Decide

You choose one method or another for a product when you set it up in the inventory. From that point on, MRP will plan production based on the method you have chosen—discrete or repetitive.

Context & Relationships

Since online readers are coming from “god knows where” it is a bad idea to refer to points from other pages as if they have already read them.

Give your readers a familiar context of the new idea that you are presenting on this “new” page as if it was the only page in existence.

Before:

As we have just seen in our page about problem hair, long tresses can pull thin or fine hair down, revealing almost-bare patches. Get a short haircut, if your hair is just naturally fine, or you will have areas where your hair is thinning out. Add volume to each shaft of hair, too.

After:

If your hair is just naturally fine, or you have areas where your hair is thinning out, get a short haircut. Long tresses can pull the hair down, revealing the almost-bare patches. Next, add volume to each shaft of hair so each hair looks thicker and stays in place all day.

Each page should be able to stand on its own two feet – research shows that online readers will:

- Process new sentence more quickly

- Remember the ideas

- Retain more information

- View the sequence as coherent

Start your pages with a summary or conclusion—this will let people figure out whether the rest of the page is relevant to them:

Before:

In a recent study, we challenged our participants to set up a candle so it would light up the whole desk area, a task that demanded people find a way of attaching a candle to a screen behind the desk. We gave 15 participants some candles, tacks, matches, and boxes, without anything inside; we gave another 15 participants the same materials, but put the candles in one box, the tacks in another, and the matches in another. The first group, having never seen anything inside the boxes, felt free to put a candle inside a box, attaching the box to the screen by hot wax. The group who saw the boxes as containers for the supplies never realized they could use a box as a platform. They were stuck with the limiting idea that the boxes could act only as containers.

Thus, a person may get fixated, adopting the point of view so vividly presented by a demonstration or display, and never letting go. Our study proves that although a diagram, display, or demonstration may help someone understand a solution or function, that very success can limit the person’s imagination when dealing with another problem.

After:

A diagram or demonstration may help someone understand a solution or function, but limits the person’s imagination when dealing with another problem. The person may get fixated, adopting the point of view so vividly presented, never letting go.

In our study, we challenged our participants to set up a candle so it would light up the whole desk area, a task that demanded that people find a way of attaching a candle to a screen behind the desk.

- We gave 15 participants some candles, tacks, matches, and boxes, without anything inside.

- We gave another 15 participants the same materials, but put the candles in one box, the tacks in another, and the matches in another.

The first group, having never seen anything inside the boxes, felt free to put a candle inside a box, attaching the box to the screen by hot wax.

But the group who saw the boxes as containers for the supplies never realized they could use a box as a platform. They were stuck with the limiting idea that the boxes could act only as containers.

Designing Chunky Paragraphs

We need to look at our paragraphs as chunks of information that will satisfy our users’ needs.

Each new paragraph should:

- offer a different point

- look like a different object visually

- provide an answer to a question

- contain about three sentences—paragraphs that are only two to three lines are much easier to skim, allowing the user to pick up relevant information from each paragraph

- Use short words referring to concrete ideas—this helps the user pick up the main ideas from the paragraphs

- Use words or sets of buzzwords that are supportive to the main idea of the paragraph

Designing paragraphs like this will allow that the reader will organize the points in their mind and not miss the succession of points by them being blurred together in the same paragraph:

Before:

We balance out the acidity, thickness, and taste, when we put together a coffee blend for a mild, bold, rich, or casual impression. We bring together beans from different countries, each with its own flavor. Of course, sometimes we serve coffees that are “single-origin” because all the beans come from one country, in one season. We think these beans are tangy enough to stand on their own. So you can see that we brew both single-origin and blended coffees. Why do we do that? Like grapes, coffee beans change their aroma, acidity, body, and flavor from year to year, and from one climate to another.

After:

We serve both single-origin and blended coffees. How come? Like grapes, coffee beans change their aroma, acidity, body, and flavor from year to year, and from one climate to another.

We brew some coffees that are “single-origin” because all the beans come from one country in one season. We think these beans are tangy enough to stand on their own.

And we serve blends of coffees bringing together beans from different countries, each with its own flavor. In this way, we balance out the acidity, thickness, and taste, for a mild, bold, rich, or casual impression.

As you write your paragraphs, pay close attention to how your paragraph is organized from:

- the key word that frames the idea or topic

- the sentence as a whole idea or topic

- the entire paragraph that gives the reader the information they seek

This portion of the Premium Design Works website is written by Mike Sinkula for the Web Design & Development students at Seattle Central College and the Human Centered Design & Engineering students at the University of Washington.

Social